SOME TIMERULES EXPLAINED

“The rules of time travel have been written not by scientists but by storytellers.”

— James Gleick, Time Travel: A History

When you unravel time and bid readers to “come away with me,” you can’t just wing it. Even if “plausibility,” (subject of a future blog) is off the table, traveling through time has to make sense, sort of. You are defying the laws of physics, breaking time’s one-way arrow, but you don’t want just anything to happen. There have to be rules.

In writing TimeLiners, I started with the rules. Even before Chapter One’s Pioneers set off for 1927, I had ten TimeRules on my iPad. I made them up but was happy to credit the sinister Timemaster. As revealed in Chapter Three, his rules begin:

1. TimeLiners travel only into the past, never the future.

But why? Why not follow the lead of H.G. Wells who sent his “Time Traveller” to the year 802,701 A.D? Why not send time tourists to the 25th century to watch some Tolkien type warlords battle over a dystopian future? A couple of reasons. . .

First, I don’t like futuristic fantasies, those Marvel Comics turned into prose. Just never my style.

Second, consider how the future is regarded in our own dystopian decade — with dread. Ten billion people sweating it out on a sizzling planet? Pandemics? AI nightmares? All those rough beasts slouching towards Bethlehem? Feel like heading there for a fun vacation? I didn’t think so.

Luckily, in making rules for something so slippery as Time, I had a higher authority — technology. IF mass time travel were possible, TimeLiners would have built-in limits. Time Jockeys could not take passengers into the future because it hasn’t happened yet. There is no “where” there. And as machines running on — whatever — even the miraculous TimeLiners could not travel on forever. Hence Rule #5.

#5 — Under current technology, the farthest travel is 1850, the nearest the day before yesterday.

Many time travel novels send characters back centuries. Visit King Arthur’s Court, how romantic! Meet Leonardo, how cool! But technology would make such epic journeys beyond range. Just as air travel, in its first decade, was confined to a few hundred miles, TimeLiners couldn’t travel to some distant forever. Not at first. Disappointed? Don’t blame me. Them’s the rules.

Fair enough, but what about. . .

Rule #3. TimeLiners travel only in time, not in space.

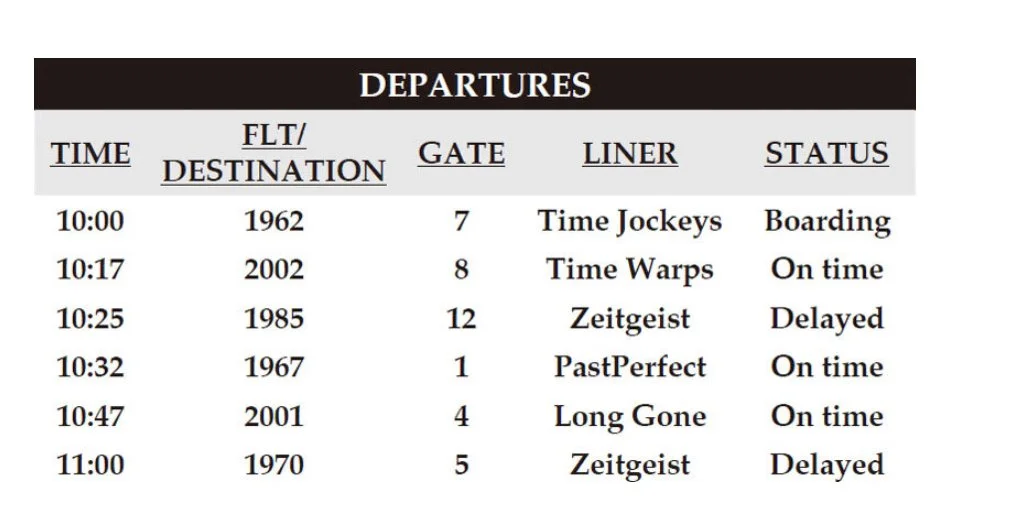

Want to visit Hemingway’s Paris? First you have to fly to Paris. Then board Le Temps Perdu Flight 1925. Unlike distance, technology did not dictate this spatial rule. I made it to set the limits one needs to craft a story.

Had Casey Clement set out from SFOT, bound for any year back to 1850 and to any where, her travels would have been far too free. Casey might have enjoyed drinking absinthe with Zelda Fitzgerald, but I needed her stateside. Because I know more about America’s past than any other, I could weave a tighter plot than in some timeworld free-for-all. Even if it meant managing tight schedules to get characters in and out of certain places, certain years, I was thankful for Rule #3.

Finally, consider the most controversial rule.

Rule #4: History is a fixed march not a work in progress. Having already happened by the time you arrive, history will proceed unchanged. There may, however, be slight disruptions in the present caused by meddling in the past.

This one flies in the face of time travel tropes. Every other work in this overcrowded genre plays off that old Star Trek episode. You know the one. Where Kirk and Spock beam down to a planet, change something so small they don’t even notice, and it changes the future. And suddenly there is no Starship Enterprise to beam them back up. What happened, Mr. Scott?

I’ve been surprised at how readers chafe at this rule. Can’t change the past? An outrage! As if there’s no other reason to go back in time other than to redeem the present. I disagree, again for a couple of reasons.

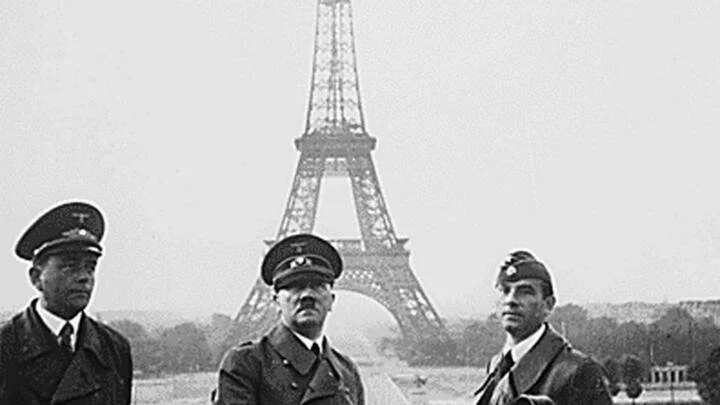

First, it’s a tired plot twist. Kill Hitler and save millions. Stop John Wilkes Booth and save Lincoln. Etc. Etc. Done to death.

Then there’s plausibility again. No one knows how tinkering with the past would change the present. If you killed Hitler, would no other Nazi step up? Had Lincoln survived, would no other assassin. . . Rather than re-open that stale can of worms, I said “no.” You can’t change the present by tinkering with the past. See pages 61-62 for further explanation.

But if no one knows how past and present are linked, why not have fun? Surely the arrival of thousands in the past would have some effect on the present. Let’s surprise ourselves. Enter the “slight disruptions” that Rule #4 predicts.

Surprise! Simon and Garfunkel never met. Both became personal injury lawyers.

OMG! — Beyoncé is a dude now.

How did that happen? Rule #4. And the disruptions only get stranger, threatening to create a world still more bizarre. Don’t blame me. The rules, the rules. . .